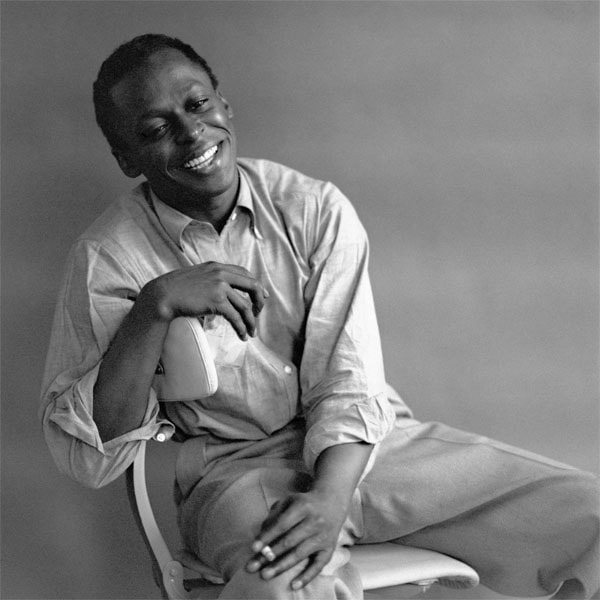

Miles Davis: Part I

The name Miles Davis is synonymous in jazz. Not only one of the most important figures of American music in the 20th century, but also one of the most controversial. Davis changed the course of the music at least five times; his keen ear for seeking new talent, allowing them to bring their individuality to his groups produced some of the most incredible recordings in the genre. Davis penchant for unusual behavior outside music, love of women, boxing, painting, and fast cars, intrigued many, while others despised him. Outside of all that, the chances he took in music are the most important thing to focus on.

Born on May 26, 1926 in Alton, Illinois, Davis was part of a middle class family. Davis’ father was a well known dentist, and bought Miles’ first trumpet at age 13. A fan of trumpeter Harry James he experimented playing with a wide vibrato, a trait corrected by his teacher Elwood Buchanan. Davis had a scholarship to the prestigious Julliard School of Music after he finished high school, although his main reason to come New York was tracking down alto saxophone innovator Charlie Parker. Miles had appeared on a April 24, 1945 session of vocalist Rubberlegs Williams, but his real exposure came on several sides made with Parker on Dial and Savoy. At this early juncture, Davis’ trademark, rich, warm tone was present although initially his lines reflected the influence of Dizzy Gillespie, whom he replaced in Parker’s quintet. In 1948, a while after leaving Parker’s group, Miles would make his first breakthrough: leading a nonet session arranged by Gil Evans, who until his 1988 passing, would remain a lifelong advisor to Davis. The style of the music of the session was a stark contrast to the frenetic bop pace, with more relaxed tempos, and plenty of composed sections. Davis was the face of the so called cool style, along with others such as baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and pianist Dave Brubeck.

In 1949, Davis began a five year relationship with Prestige records. In 1954, Davis was considered to be at the forefront of another new Jazz style: hard bop, or what vibraphonist Milt Jackson called original funk. Hard bop sought to bring Jazz back to the people in a sense, although an extension of bebop, the music contained stronger R&B, gospel and blues references than it’s predecessor. Davis’ famous 1954 session Walkin , a jam session with trombonist J.J. Johnson, swing to bop tenorist Lucky Thompson, pianist Horace Silver, bassist Percy Heath, and drummer Kenny Clarke. The session coincided with the advent of recent 12″ long playing LP approximating closely the way musicians would perform live. The album, along with the equally well known Bags’ Groove placed Miles with the cream of the crop of other hard boppers the likes of Silver, and Art Blakey Davis’ famous marathon sessions resulting in Workin’, Cookin’ Relaxin’ and Steamin’ concluding his Prestige contract. his debut for Columbia, Round About Midnight are cornerstones of the genre as well.

In 1957, Miles again collaborated with Gil Evans for Miles Ahead, a ground breaking record with a large band, that would be the first of 4 collaborations between 1957-64. The combination of Davis’ horn combined with Evans’ colorful backdrops, are on par with the best European art music, successful without diluting the art. By 1959, Davis grew tired of music that was chord changed based, which lead him to his next game changing moment. Davis’ sextet with John Coltrane, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley on alto saxophone, pianist Bill Evans, (Davis’ current pianist Wynton Kelly sat in on “Freddie Freeloader”) bassist Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb on drums recorded his crowning achievement Kind of Blue during two sessions in 1959. The music based on modal principles, or improvising on different scales, rather than chord changes. The music truly opened up in a new way, although Davis offered glimpses of a flirtation with modality on tunes such as “Max is Making Wax” (issued on the 2 disc Legacy version of Round About Midnight ) and Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way” (on Workin’) and more explicitly, the title track to 1958’s Milestones. Bill Evans impressionistic intro to “So What”, opened up a new way for pianists to think about harmony, and “Flamenco Sketches” offered each soloist a chance to work with a series of different scales. As overly technical that this may sound to a casual listener, the music on Kind of Blue contains a beauty that transcends boundaries, making it the most popular Jazz record of all time. The vocabulary presented on this record is standard for musicians worldwide.

The 1959-1963 period of Davis’ career would continue to mold the hard bop and modal combination to perfection. Unfortunately it must be said that around the time of the release of Kind of Blue Davis was beaten outside of Birdland by a drunk police officer, who had claimed he could not stand outside on the street. The racist undertones of this egregious assault, cemented Davis’ mistrust during the civil rights movement. Critics have argued that Davis’ music during this time, and the future was an assertion of the black experience, and the Birdland incident was a microcosm of the American racial divide at time.

In 1963, for Seven Steps to Heaven Davis recruited Herbie Hancock, on piano, bassist Ron Carter and young phenom 17 year old Tony Williams along with tenor saxophonist George Coleman. Two tracks, featuring the debut of the Carter-Hancock-Williams rhythm section offered glimpses of a new direction, influenced in part by avant gardists such as Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman. In the new approach of the rhythm section, Williams began to play with time and meter as if it was an elastic band, with Carter and Hancock instinctually reacting at will adding exciting new dimensions to the music. Davis found George Coleman a bit too conservative for the music, though this group made the undisputed classics My Funny Valentine: Miles Davis in Concert and Four and More recorded on February 12, 1964 live in New York City. The former album containing a beautiful, radical reworking of the standard “My Funny Valentine” (first heard by Miles in 1956) bolstered by Tony’s fluid changes between swing, straight eighth and Latin rhythmic feels. For comparison, follow the straightforward version he recorded in 1956 shown below and then the radically deconstructed 1964 version. The latter turning something so familiar into a chance taking improvisatory vehicle. The next installment will focus on the Second Great Quintet, In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, through to Miles’brief retirement. Here is Part II.

I have been the staff writer for the New York Jazz Workshop School of Music blog in midtown Manhattan since 2014, and that has broadened my freelance writing skills considerably. In addition to writing artist bios, and articles of interest that pertain to the mission of the school, I have interviewed (in print on the site) legendary guitarist and NEA Jazz Master Pat Metheny, trumpeter Cuong Vu, and in 2015 embarked on producing a podcast for the school where I have achieved my dream and interviewed jazz giants such as Dave Liebman, Lenny White, rising talents like Thana Alexa, Logan Richardson, guitarist and bassist Brian Kastan, among others. I also work on SEO optimization for the blog. In 2015 I started my blog Jazz Views with CJ Shearn, and have written liner notes for 5 time Grammy winner and Oscar and Golden Globe nominee, Antonio Sanchez (for his latest recording “Channels of Energy”) and guitarist Gene Ess for his latest recording, scheduled to be released in November 2018.

My passion for jazz music is what drives me, which is an interest I’ve had since I can remember. I initially began writing about jazz at the age of 13 for my high school newspaper, and in my late teens contributed occasionally to jazzreview.com. In college I was member of the Harpur Jazz Project which brought jazz acts to campus. I’ve also contributed in the past to AllAboutJazz where I was mentored by John Kelman. I decided to focus on my passion for jazz music journalism after a job in the social services field as a caseworker went south, and as a person with a physical disability I work on going against the odds, living independently and having accomplished things people had said I’d never do.